Anaconda Webinar Notes - 2022 Predictions

Written on December 15th, 2021 by Daniel E

In a bid to stay up-to-date with the latest developments in the field of AI, I attended a webinar organised by Anaconda. In this webinar I joined Peter Wang, Co-Founder and CEO at Anaconda, Christine Doig, Director of Innovation for Personalized Experiences at Netflix, Soumith Chintala, Research Engineer at Meta AI Research and Chris Albon Director of Machine Learning at Wikimedia Foundation as they discussed their journeys through their AI/ML/DS careers and what 2022 holds for these fields.

In this article I refined my webinar notes into a piece of writing that I and others can revisit.

Here’s what I learnt:

What’s Next in Data Science, AI, and ML: How far we’ve come

DS and ML have grown more mainstream, but it wasn’t long ago that you would be considered a wizard if you developed a new machine learning algorithm and wrote a scientific article on it. The bar to make an impact was very low. Now everyone will have heard of, seen or used ML, and right now in industry numerous models are being managed and running continuously at scale, in production every day. On the scientific side you will see more algorithms being developed too.

Before, it was only one person (a DS potentially) that would deal with an ML project end-to-end, data to prediction. In the present day that process is way more fragmented yet integrated at the same time. AI/ML has started to become a part of the culture of a company, with design and creative teams also being drawn into such projects.

Another way of putting it is you have multiple levels. The first is software engineering, where you could say it is proven that a shopping cart icon increases sales, and as a result you want a shopping cart. You would then have a team implement a shopping cart. On next level, the one that we’re discussing, we have AI/ML, which is still in an exploratory phase. At this level you may say you want to predict something, but later, after investing manpower and resources, you might find out it is actually impossible/infeasible to predict that certain something you want to predict as part of your product. This level involves a lot more uncertainty, to the point where some projects become bets essentially. These bets can pay off quite handsomely if a certain hypothesis is proven, but at the same time a company investing resources and manpower into something that turns out to be impossible is something to be aware.

People working these two levels see the lifecycle differently, despite the latter having evolved from the former. The word production can mean multiple things. In ML the lifecycle is so much more data-oriented. You have to version your data, keep track of & validate your model and ensure reproducibility all the way through to production etc. Timescales and testing will be different too.

This uncertainty on what can and cannot be done is both a blessing and a curse. It may be that a lot of time and resources are wasted on impossible tasks, but this is what drives innovation. This potential high reward (e.g. a new Netflix recommender algorithm that adds viewer hours) makes for continued innovation. Once an idea is proven to be achievable, other ideas will start sprouting up and this exploratory process repeats itself.

Soumith/Meta’s three buckets:

- 1st - ML practitioners using modelling, GPUs, TensorFlow, think about the entire lifecycle very differently. Stable datasource, train model + tuning, changing architecture hoping results change.

- 2nd - Data scientists, infrastructure – innovation for them is changing a few hyperparameters, feature selection, tabular data, almost BI stuff.

- 3rd - People working out of laptops and not out of RedBricks clusters, quickly preprocessing a csv, whipping up a neural net/random forest instantly with a skl or TensorFlow followed by a report.

Majority of ML/DS practitioners reside in third bucket.

There are 3 similar levels at Netflix too: Research Scientists, Algo/ML Engineers and Data Scientists.

In the past people working in the first two buckets were few and far between. That’s changed now, and you have a ton more industry (the first two buckets).

Opensource vs commercial development

If you give people open-source tools, you will have crowdsourced innovation and “low hanging fruit” problems will get solved first, albeit never completely finished and bug ridden. A tool a such problem will be worked on until it is good enough for people to use and say “it is no longer viable to create a uniform/polished commercial product around this problem.”

Peter: Will there ever be a too big of a product-to-be/problem to be solved that open-source cannot solve?

- Say you’re builing a vertically integrated B2B solution. Developing a such solution will have a top-down feel to it. Your sales cycle is: “I go to CEOs and CTOs and hope they take the product into their company and they integrate it”.

- Say you are now building B2B/B2C solution in an open-source setting. The process is much more organic. Your main selling points are open-source, transparency, ease of use, and an existing ecosystem around this product.

There is a big difference between what these products can achieve, as open-source products without commercial motivations will have limitations in terms of what they can achieve… Soumith sees open-source as a strategy on how a company might want to sell products, an effective one at that, as you can compete with non-open-source providers. Open-source will likely lack a level of support too.

If you’re doing open-source as a hobby, you won’t be able to build anything that is vertically integrated, because that requires a level of coordination and funding that open-source does not have.

Right now we are seeing massive discrepancies across these two domains, but the two aren’t fundamentally at conflict. You will see large amounts of money being funelled into algorithms that can drive growth in a business, but you will also see underfunded projects like NumPy that are widely used, with only 3 or 4 devs working on them. Going back to the betting analogy, this might be Numpy’s way of offsetting risk, by slowly developing functionalities and monitoring how well they are received. Big companies (Netflix, Google) don’t have to worry about this, but smaller companies do.

There is a difference in what the two can achieve. For example open source projects without commercial motivations have certain limitations.

Numpy and scikit became so highly modular and widely adopted because they slowly evolved out of necessity. If 10 years ago a billion dollar venture were to say “Here’s a small loan of a billion dollars, go and build a sprawling DS ecosystem” it would likely not have been possible, as you can’t force evolution. Still, you see that happening with MLOps these days. It has worked well so far.

One could say we may be yet to understand what best open-source-commercial balance one can have given the size/cost of implementation of a desired project.

The future

CEOs and managers can definitely set out to develop a new algorithm that can be deemed a potential money cow, do sales pitches, spend months on research and hire a whole team of designers, SREs, project managers etc. Alternatively, and perhaps more wisely, a company can go and obtain API access to an already existing product from a company that has already explored a similar task. That way they can build on This way way of doing things has been seen to work (e.g. the modularity and widespread use of Numpy) and could be the future of doing things in this field. This could be attributed to the reduced risk of building a product i.e. the bet I alluded to earlier. Bets are now cheaper in a way, thanks to open-source and its encouraging businesses to stay near the boundary of knowledge that we have, rather than venturing way out into the unknown.

As was the case in the past with this entire field, we now see few and far between people that can talk about explainability and ethical AI. It is an old academic field but a very nascent practical field. You will find very few people to have a conversation with on these topics. As Christine put it very succintly, right now we’re only poking at the black box and nothing more. This is not cause for discouragement however, we are early in this journey.

Soumith is looking forward to further development of Python ecosystem. We use so much multiprocessing and we know the fundamental problems. It’s not a software or library, but it’s one of those things. Looking forward to seeing Python become a performance rich language as that is a fundamental bottleneck right now. productiveness when they want performance. Numba, accelerators, pytorch compiler, these tools are not there yet in terms of giving everything. Would like this side of things to mature more. Faster like C++ and stuff. Goal is “built with Python” not “hammered with Python”.

Daniel’s take on this

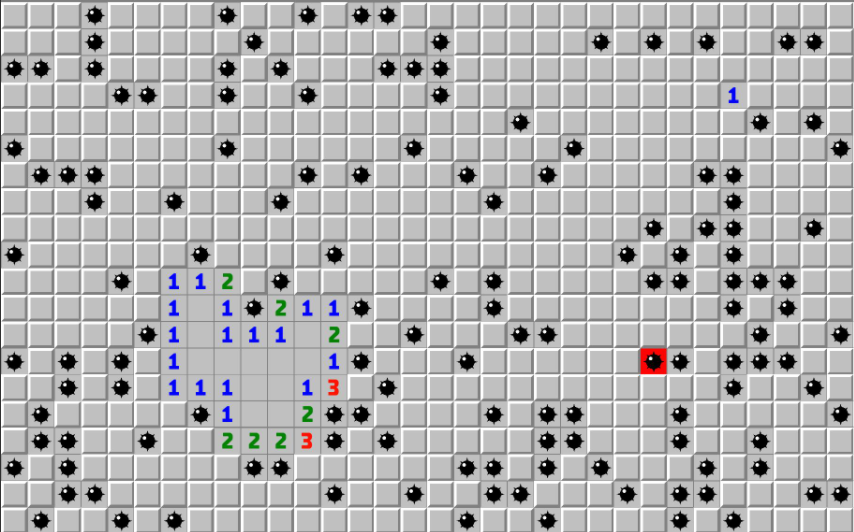

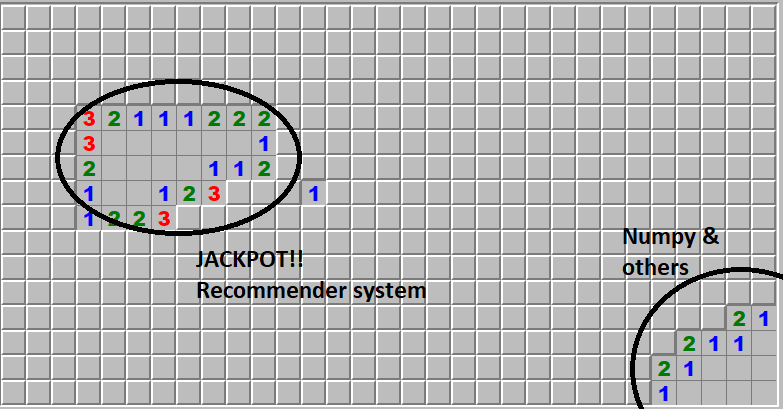

The way I see it is: When it comes to developing new tools/products like Numpy or an AI recommender algorithm, be it the open source way or by the business community, development is like a game of Minesweeper. When teams/individual programmers first start out they start by randomly clicking a cell at the beginning of the game, or, they start with an idea. The next steps in the game would be clicking another cell in a different area (high risk, high reward), or systematically working with known information (how many mines are near the area you’ve unlocked) and building on these ideas (e.g. building a NumPy accelerated linear algebra module).

These high risk high reward bets that have been talked about so much can be likened to clicking an unknown cell in the middle of the map. Two things can happen:

- you either hit a mine, i.e. you lost the game, your investment and your and others’ time

- you don’t hit a mine and you learn this idea is feasible. On top of that you find there’s a whole new area of clear land, i.e. further possible developments to this new groundbreaking algorithm you have developed that can complement your business model, i.e. handsome monetary rewards

What these experts say is the future will unfold in a way akin to the optimal Minesweeper mine clearing strategy, where mines are systematically flagged and new areas of development are discovered with ease, slowly and safely. While this takes longer, it yields continuous rewards for ALL.

Keywords

notes, data-science, machine-learning, open-source, explainability, Meta, Netflix, Wikimedia, Anaconda